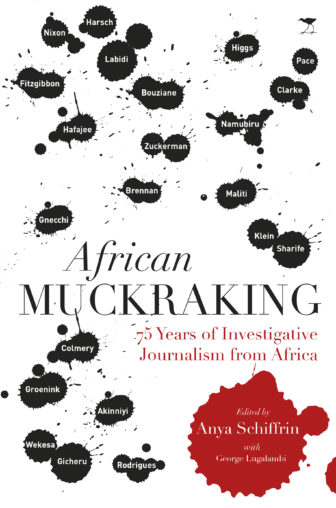

Editor’s Note: African Muckraking: 75 Years of Investigative Journalism from Africa is a collection of investigative and campaigning journalism written by Africans about Africa. This collection of 41 pieces of African journalism includes passionate and committed writing on labor abuses, police brutality, women’s rights, the struggle for democracy and independence on the continent. Each piece of writing is introduced by a noted scholar or journalist who explains the context and why the journalism mattered. Edited by Anya Schiffrin with George W. Lugalambi, African Muckraking is a must-read for anyone who cares about journalism and Africa. The book is being launched this week during #GIJC17, the 10th Global Investigative Journalism Conference, in Johannesburg. Below is an excerpt.

Editor’s Note: African Muckraking: 75 Years of Investigative Journalism from Africa is a collection of investigative and campaigning journalism written by Africans about Africa. This collection of 41 pieces of African journalism includes passionate and committed writing on labor abuses, police brutality, women’s rights, the struggle for democracy and independence on the continent. Each piece of writing is introduced by a noted scholar or journalist who explains the context and why the journalism mattered. Edited by Anya Schiffrin with George W. Lugalambi, African Muckraking is a must-read for anyone who cares about journalism and Africa. The book is being launched this week during #GIJC17, the 10th Global Investigative Journalism Conference, in Johannesburg. Below is an excerpt.

Sheila Kawamara in the Killing Fields of Rwanda

Introduction by Lydia Namubiru

At the start of the Rwandan genocide, many foreign journalists were evacuated from the country’s capital, Kigali, to the safety of Nairobi, in neighboring Kenya. One Ugandan journalist, Sheila Kawamara-Mishambi, did quite the opposite. She walked into her editor’s office and asked to be sent into Rwanda.

For most of us, the story of the Rwandan genocide begins on April 6, 1994, when the plane carrying then-president Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down, killing all on board and sparking mass killings on the streets of Kigali.

Kawamara had been on that “beat” for nearly four years. Married to a Ugandan army officer, she learned on the night of October 1, 1990 that scores of soldiers of Rwandan descent had deserted the Ugandan army at once, with arms. They then invaded their “homeland” with the intention of overthrowing Habyarimana’s government. In September 1993, seeing that the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), formed by the deserters, hadn’t overthrown Habyarimana but were still intent on war, Kawamara left Kampala to report on the rebel group from its bush base in Mirundi, Northern Rwanda. That initial contact would prove invaluable to get access to the killing fields of Rwanda after the genocide began seven months later.

When the massacres erupted, New Vision, Kawamara’s employers, first resorted to re-publishing reports from the BBC’s Focus on Africa and Reuters. “Here we were, running stories by Reuters from Nairobi!” Sheila recalls. The Kenyan capital is 469 miles (nearly 755 kilometres) from Kigali, Rwanda.

Sheila Kawamara

Sheila implored her editor: “As journalists, we can’t abandon our credibility by depending on these accounts. We have to go in there (into Rwanda).” The editor, William Pike, was wary of the idea. The Kampala-based newspaper had never sent a reporter into a war zone. It neither had insurance nor a security plan for that eventuality. Having explained the risks, Pike let Kawamara sleep on her decision. When he contacted her the following afternoon, she was still determined to go and he okayed her trip. “Once you have signed your own death warrant, then you need a friend to go with it,” Kawamara jokes. She convinced a freelance photographer, Cranmer Mugerwa, to join her on the trip.

The first stories she filed from Rwanda didn’t run. The editors in Kenya simply couldn’t believe them. Surely, she had to be exaggerating: 300 bodies in a church; 500 bodies in a mass grave elsewhere! This was the Rwandan countryside. How could the paranoid soldiers of the falling Habyarimana regime, who were blamed for the killings on the streets of Kigali, reach that far and with such force?

Over the phone, Kawamara’s editors asked her to provide pictorial evidence of her accounts. She travelled back to Kampala with the gruesome images, and the story broke that massacres were taking place countrywide. Kawamara gave a round of interviews on the international media circuit before returning to Rwanda to continue reporting on the genocide for New Vision.

On her second trip, New Vision assigned its top photographer, Jimmy Adriko, to the story. International journalists joined the group. “Now I could take advantage of their cars and security equipment,” Kawamara recalls with wry laughter.

Embedded with the RPF, she stayed in Rwanda and reported the story right up to July19 when the new government was sworn in. Along the way, she saw such horrors that, for years, she could not bring herself to go back to Rwanda. When she went back in 2005, she could not sleep alone at night. “It’s beautiful now, but in my mind, every place was littered with bodies.” For reassurance, she begged her way into the bed of a woman she was traveling with. “Trauma. That’s something journalists never think about. We just go after the story,” Kawamara, 52, notes with hindsight.

The following article is one of many stories Kawamara published on the genocide. It’s the ultimate eye-witness account, traumatic for the journalist as well as for her news subjects. Led by the stench of decomposing human flesh, a group of four journalists approaches a recently filled mass grave. Then, from inside the grave, voices call! The journalists aren’t hearing metaphorical voices. Inside that burial place filled with a mass of decomposing bodies are 10 living people, who have witnessed even more atrocities than the war journalists. They saw 800 people hacked to death. They carried their bodies into that grave.

Journalists, RPF, Rescue Survivors From Mass Grave

Sheila Kawamara, New Vision, April 19,1994, Murambi, Rwanda

Foreign journalists in Rwanda, together with some soldiers of the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), on Saturday, exhumed four people from a mass grave at Kizigulo Catholic Parish, Murambi commune, north eastern Rwanda.

Six others were yet to be rescued from the pit estimated to be 50 meters deep with over 800 decomposing bodies of massacred civilians who had taken refuge at the mission. By the time journalists left the scene, local people had been mobilized to continue with the exercise.

According to one of the victims, Jean Busheija, who looked dehydrated and cried out helplessly for water, he and the other survivors had been forced to carry the 800 corpses.

“I jumped inside the pit with the last body to avoid being hacked to death by a machete-wielding Interahamwe who stood at the pit’s mouth,” Busheija narrated in Kinyarwanda with difficulty.

He said they ferried the bodies from 12 pm to 6 pm. He said the people were massacred on April 11, after the government soldiers together with the Interahamwe forced the Spanish Missionaries to abandon the displaced people at the church.

Those killed included Tutsis and Hutus opposed to MRND, the late president Habyarimana’s political party.

“They came and asked for our identification along with all the money we had on us. We were then told to kneel down as they hacked everybody to death,” Busheija said.

The rescued people had their eyes partly eaten by flies and they carried a stench of decomposing bodies.

The four journalists, who included Ugandans and a Swiss, discovered the survivors when they were being conducted around by RPF to assess the extent of the atrocities committed by the fleeing Rwandese soldiers.

The RPF forces took over Murambi commune on Friday after an eight-hour battle with government forces which had put up strong resistance. The RPF commander of the north-eastern front, Col. William Bagire, told journalists that government troops at Kizigulo were heavily armed. Mutara sector of the RPF, which is fighting for control of eastern Rwanda, has so far lost eight men and suffered 11 casualties. According to Bagire, at Rukara, RPF discovered 1500 people locked up in Gahini Protestant Church. Another 300 were reported to have been dumped in a pit latrine. Journalists, however, could not confirm these incidents.

Asked as to when RPF was likely to overrun Kigali, Bagire said that was not a priority. ‘I cannot tell you when we will be in Kigali but we will definitely get there,’ he said with confidence, adding that he had a mission to bring eastern Rwanda under effective control of the RPF.

Mutara RPF chief said, apart from the reported atrocities in Kigali, thousands of innocent civilians are being murdered in the countryside. ‘The world knows about killings in Kigali but not the killings in the countryside,’ he said.

Location of Kigali (in dark red) in Rwanda.

Most of these killings by the presidential guard, elements of the Rwandese army and the Interahamwe, were Tutsis and Hutus opposed to the late president.

Some identity cards were discovered by journalists at Kizigulo without the bearers’ photographs.

As journalists were taken around Murambi commune, which had been overrun by the RPF the previous day, bodies lined the Kigali-Kagitumba road.

The excerpt from African Muckracking is posted here with permission.

Anya Schiffrin teaches and runs the Technology, Media and Advocacy Program at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs in New York. She c0-edited African Muckraking, was the editor of Global Muckraking: 100 Years of Investigative Journalism from Around the World (New Press, 2014) and developed Massive Open Online Course on Global Muckraking, which drew on her teaching and the books.

Anya Schiffrin teaches and runs the Technology, Media and Advocacy Program at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs in New York. She c0-edited African Muckraking, was the editor of Global Muckraking: 100 Years of Investigative Journalism from Around the World (New Press, 2014) and developed Massive Open Online Course on Global Muckraking, which drew on her teaching and the books.

George W. Lugalambi (PhD) is a media development specialist and researcher based in Kampala, Uganda. A former journalist and newspaper editor, he chairs the panel of judges for the Uganda National Journalism Awards. He headed the Department of Journalism and Communication at Makerere University from 2008 to 2011. He was with the Natural Resource Governance Institute from mid-2011 to early 2017 as manager of a capacity development programme for strengthening media oversight of the extractive sectors of oil, gas, and mining. He is the lead researcher for a long-term media monitoring project of the African Centre for Media Excellence that tracks and analyses coverage of public affairs in Uganda. He contributed to Global Muckrakers (2014) and co-edited Africa Muckraking (2017).

George W. Lugalambi (PhD) is a media development specialist and researcher based in Kampala, Uganda. A former journalist and newspaper editor, he chairs the panel of judges for the Uganda National Journalism Awards. He headed the Department of Journalism and Communication at Makerere University from 2008 to 2011. He was with the Natural Resource Governance Institute from mid-2011 to early 2017 as manager of a capacity development programme for strengthening media oversight of the extractive sectors of oil, gas, and mining. He is the lead researcher for a long-term media monitoring project of the African Centre for Media Excellence that tracks and analyses coverage of public affairs in Uganda. He contributed to Global Muckrakers (2014) and co-edited Africa Muckraking (2017).

Sheila Kawamara Mishambi was the founding executive director of Uganda Women’s Network. She previously wrote for New Vision, where she was among a group of daring Ugandan journalists who headed into Rwanda to cover the genocide two days after then-President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down.

Sheila Kawamara Mishambi was the founding executive director of Uganda Women’s Network. She previously wrote for New Vision, where she was among a group of daring Ugandan journalists who headed into Rwanda to cover the genocide two days after then-President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down.